Realism and optimism. Are they a healthy combination?

Casting an eye over media headlines each day, it’s difficult not to be confronted by language which can provoke distress. Repeatedly seeing terms such as: ‘attacks, turmoil, division, alienation, heartbreak, outrage, condemnation, threats, invasion, panic, estrangement, aggression, brutalism, risk, grief and fear’ can result in a view of the world that is alien and terrifying.

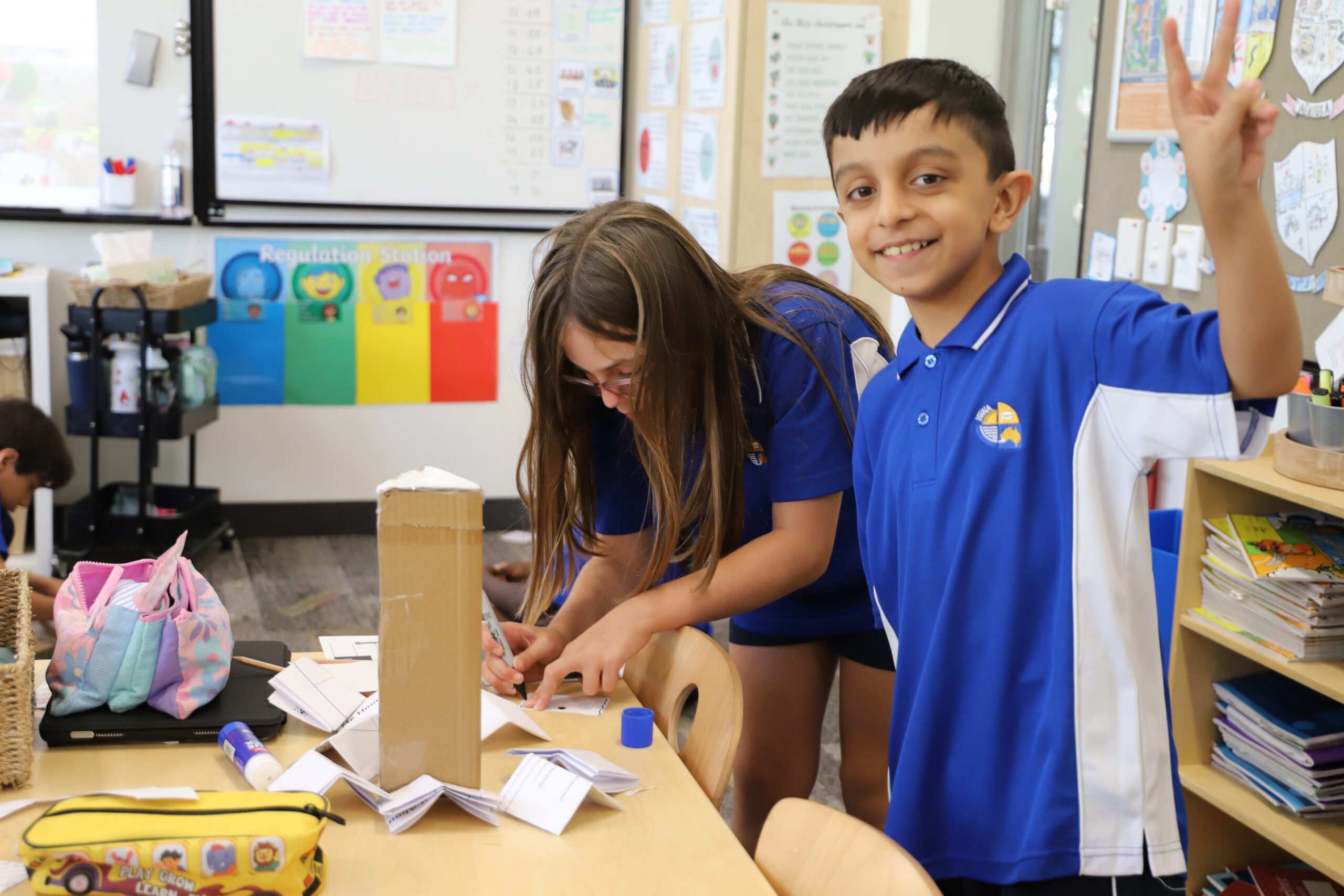

During turbulent and unsettling periods, it can be both salutary and comforting to pause for a moment and reflect upon all that we can be grateful for. At ISWA, students from a broad spectrum of nationalities, ethnicities, faiths, regions, socioeconomic backgrounds and experiences come together in a welcoming, safe, warm, inclusive environment. This is due to our culture which emphasises relationship-building, empathy, a solution focused approach and ethical decision-making. We respect one another, our environment, our collective histories and ourselves.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s speech at the Sydney Opera House on January 22, 2026, spoke of us ‘affirming the shared values of unity, compassion, and resilience that define Australia.’ and these resonate with our ISWA Purpose and Commitments the goals of which are: |

‘…to be enriched by the perspectives of others’, to ‘embrace the opportunity to see the world from various perspectives. We respect the ideas and cultures of others. We create new understandings through connections. We are committed to a diverse, equitable, and inclusive society, and maintaining a global perspective’.

These beliefs and values align with the IB philosophy on peace which is that ‘…students combine creativity, activity and service to achieve something for their community.’ It ensures that IB schools ‘…nurture critical thinking, teamwork and problem-solving…which fosters coexistence’. The IB aims to ‘…develop inquiring, knowledgeable and caring young people who help to create a better and more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect’.

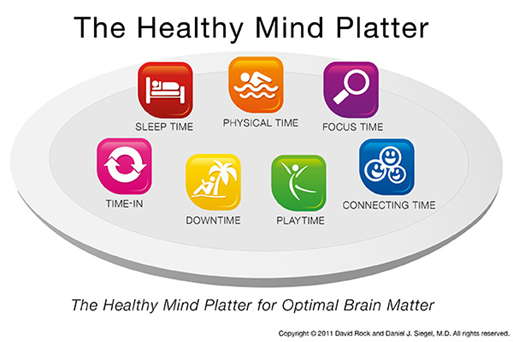

These are the foundations upon which we co-construct our days at ISWA, teaching students to arm themselves with credible information from reputed sources. They realise that confusing and perturbing things happen. They seek accurate information to become reasoned thinkers. They are encouraged in their realistic optimism.

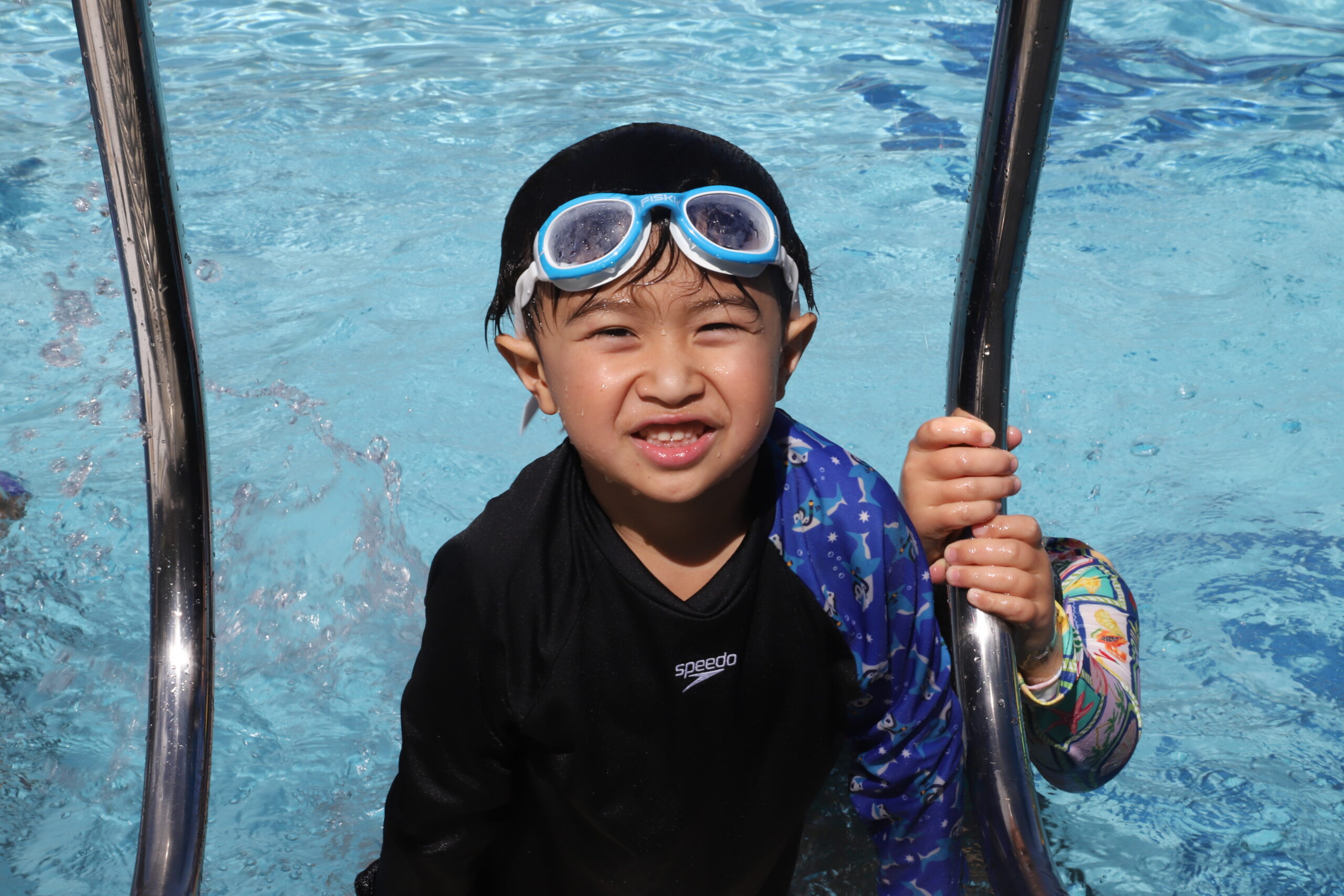

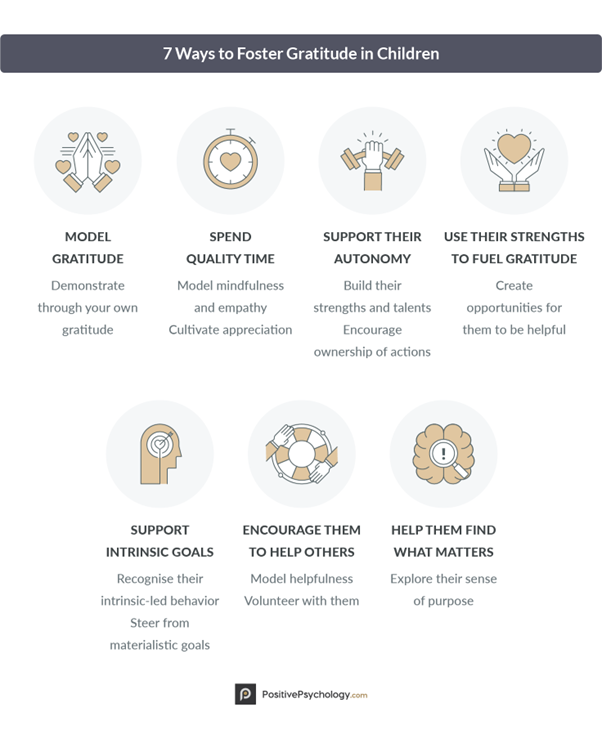

So, in the face of what can appear daunting obstacles certainty can be elusive. However, what we do know absolutely is that young people thrive on the unconditional acceptance and love of family, firm but compassionate boundaries, being heard, valued and encouraged for their efforts, not their results.

With these foundations, and our unique, multi-cultural context at ISWA, we are confident our students will have insight and passionate commitment, not to naively overlook or minimise the world’s problems. but recognise and tackle them. Issues such as hate crimes, unlawful killings, land grabs, food and climate insecurity, abuse of power, natural disasters, poverty and corruption don’t need to overwhelm and debilitate us. We can do as John Lennon sang ‘Imagine all the people sharing all the world’. We can envisage our roles in bettering society then model hope, goodwill, generosity, kindness and compassion, every day.

As Confucius said: ‘Education breeds confidence. Confidence breeds hope. Hope breeds peace’.

Christine Rowlands

School Counsellor